Purposes of an operating system:

- Abstract the hardware for convenience and portability

- Multiplex the hardware among many applications

- Isolate applications in order to contain bugs

- Allow interaction among cooperating applications and control interaction for security

- Don’t get in the way of high performance

- Support a wide range of applications, like database servers, cloud computing and etc.

In general, an operating system must fulfill three basic requirements: multiplexing, isolation, and interaction.

The old OS abstracts the resources into services as a library. Some operating systems for embedded devices or real-time systems are still organized in this way.

When the OS needs to time-share the resources of the computer, the downside of this library approach occurs. Such OS can’t make sure it won’t fail or other applications won’t fail if a program does something that we don’t want it to do, such as assessing other application’s memory.

We hope that the operating system should be able to clean up the failed application and continue running other applications. Thus, the OS must arrange for stronger isolation between different applications. However, isolation can’t be too strong, since it should be possible for processes to intentionally interact.

To achieve stronger isolation, it’s helpful to forbid applications from directly accessing sensitive hardware resources, and instead accessing by the OS services. For example, the applications interact with storage only through the file system provided by the OS instead of reading and writing the disk directly. Even if isolation is not a concern, programs that interact intentionally are likely to find a file system a more convenient abstraction than direct use of the disk.

Furthermore, it also requires a hard boundary between applications and the OS, which makes sure that applications cannot modify or even read the OS’s data structures and instructions or access other application’ memory.

Such isolation is implemented by two hardware modes of CPU which is set by a status bit in a special register.

- A hardware user mode. **In user mode, the CPU can only execute user instructions , e.g., adding numbers, etc. An application in user mode is said to be running in **user space,

- A hardware supervisor mode (i.e., kernel mode).In supervisor mode the CPU is allowed to execute privileged instructions, e.g., enabling and disabling hardware interrupts, Errors in supervisory mode are often catastrophic (blue “screen of death”). If an application in user mode attempts to execute a privileged instruction, then the CPU raises an exception that might terminate the application, because it did something it shouldn’t be doing. The software in supervisor mode is said to be running in kernel space, which is also called the kernel.

Some hardwire architectures will provide extra modes. For For example, RISC-V provides a machine mode. Instructions executing in machine mode have full privilege and a CPU starts in machine mode. Machine mode is mostly intended for configuring a computer.

Note that not all programs of the OS are in the kernel space. Shell in Linux, for example is an ordinary user program that reads commands from the user and executes them. But most key services of the OS are in the kernel. The study of the OS is mainly about the kernel which determines whether a OS is successful.

Typical kernel services include:

- process

- memory allocation

- file contents

- file names, directories

- access control (security)

- many others: users, IPC, network, time, terminals

An operating system provides kernel service to user programs through an interface . The call to such interface is referred to as a system call. Similar to a function call, except it’s now executed by kernel. Unix operating system provides a narrow interface whose mechanisms combine well, offering a surprising degree of generality. This interface has been so successful that modern operating systems—BSD, Linux, Mac OS X, Solaris, and even, to a lesser extent, Microsoft Windows—have Unix-like interfaces.

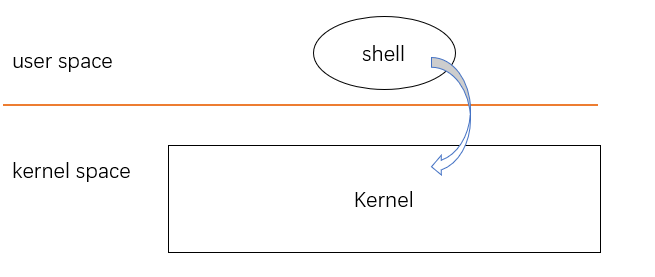

The user programs that wants to make a system call must transition to the kernel:

- The program saves registers and other state of the user space so that execution can be resumed.

- A special instruction, such as

ecallin RSIC-V, raises the hardware privilege level and changes the program counter to a kernel-defined entry point. The CPU is switched from user mode to supervisor mode. - The kernel then validates the arguments of the system call, decide whether the application is allowed to perform the requested operation, and then deny it or execute it.

- The CPU executes the kernel instructions that implement the system call.

- When the system call completes, the CPU returns to the user mode by calling another special instruction, like

sretinstruction in RSIC-V, for example. This instruction lowers the hardware privilege level and resumes executing user instructions just after the system call instruction.

It is important that the kernel control the entry point for transitions to supervisor mode and ensure that arguments are properly specified, so that a malicious application could not enter the kernel at a point of the user program where the validation of arguments is skipped.

To specify the exact system call, a system-call number is usually assigned to each system call. The user code is thus responsible for placing the desired system-call number in a register or at a specified location on the stack. This level of indirection serves as a form of protection; user code cannot specify an exact address to jump to, but rather must request a particular service via number.

Key design question is what part of the operating system should run in supervisor mode. One possibility is that the entire operating system resides in the kernel, so that the implementations of all system calls run in supervisor mode. This organization is called a monolithic kernel. Most Unix operating systems are implemented as a monolithic kernel.

In this organization the entire operating system runs with full hardware privilege. This organization is convenient because the OS designer doesn’t have to decide which part of the operating system doesn’t need full hardware privilege. Furthermore, it is easier for different parts of the operating system to cooperate. For example, an operating system might have a buffer cache that can be shared both by the file system and the virtual memory system.

A downside of the monolithic organization is that the interfaces between different parts of the operating system are often complex, and therefore it is easy for an operating system developer to make a mistake. In a monolithic kernel, a mistake is fatal, because an error in supervisor mode will often cause the entire kernel to fail. If the kernel fails, the computer stops working, and thus all applications fail too. The computer must reboot to start again.

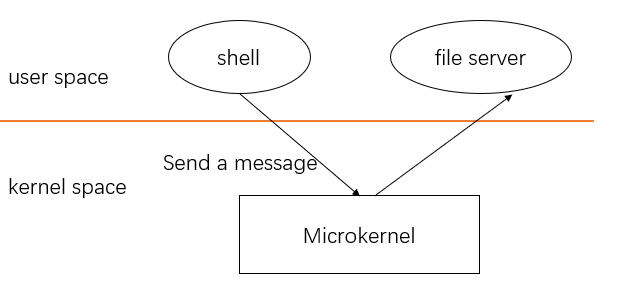

To reduce the risk of mistakes in the kernel, OS designers can minimize the amount of operating system code that runs in supervisor mode, and execute the bulk of the operating system in user mode. This kernel organization is called a microkernel.

In the figure above, the file system runs as a user-level process. OS services running as processes are called servers. To allow applications to interact with the file server, the kernel provides an inter-process communication mechanism to send messages from one user-mode process to another. For example, if an application like the shell wants to read or write a file, it sends a message to the file server and waits for a response.

In a microkernel, the kernel interface consists of a few low-level functions for starting applications, sending messages, accessing device hardware, etc. This organization allows the kernel to be relatively simple, as most of the operating system resides in user-level servers.